Reviewing Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program Payment Error Rates and Benefit Card Transactions, Part 1

Introduction

Representative Shannon Francis, Representative Bob Lewis, and Representative Kristey Williams requested this audit, which was authorized by the Legislative Post Audit Committee at its May 12, 2025 meeting.

Objectives, Scope, & Methodology

Our audit objective was to answer the following question:

- What caused DCF’s overpayment and underpayment rates for SNAP to exceed the federal government’s standards in recent years?

The original audit proposal included a second question related to benefit card transactions. We split the audit into 2 reports and will release a report related to benefit card transactions later.

The scope of our work included examining the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program’s (SNAP) payment error rates in the last few years. To conduct this work, we reviewed documents provided by the Department for Children and Families (DCF) to understand the SNAP application and verification process. We also reviewed federal and state laws and regulations to determine what steps DCF staff must take when verifying applications. We reviewed federal documents to understand how the federal government calculates the SNAP payment error rates and to determine what Kansas’s rate has been since 2003. Last, we reviewed DCF documents and interviewed DCF officials to gain a better understanding of the causes of the state’s SNAP payment errors in fiscal years 2023 and 2024.

Due to federal laws that prevent DCF from providing SNAP applications to us, we were unable to review SNAP applications. As such, we were unable to determine more specifically the errors that contribute to the payment error rates. Instead, we relied on documentation provided by DCF that notes the types of errors and the primary cause of those errors as they determined them.

More specific details about the scope of our work and the methods we used are included throughout the report as appropriate.

Important Disclosures

We conducted this performance audit in accordance with generally accepted government auditing standards. Those standards require that we plan and perform the audit to obtain sufficient, appropriate evidence to provide a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives. We believe that the evidence obtained provides a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives.

Audit standards require us to report our work on internal controls relevant to our audit objectives. They also require us to report deficiencies we identified through this work. In this audit, we compared DCF’s SNAP application verification process to federal requirements. We did not identify any deficiencies.

Our audit reports and podcasts are available on our website www.kslpa.gov.

DCF’s payment error rate exceeded federal standards in fiscal years 2023 and 2024 for multiple reasons including high staff turnover, the complexity of the SNAP eligibility rules, and inconsistent verification efforts.

Background

The Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) is a federal program that provides monthly funds to low-income families to buy food.

- SNAP provides a monthly benefit to qualifying families to buy food. SNAP recipients can use the benefit to buy food such as fruits, dairy products, snack foods, and non-alcoholic beverages. SNAP funds cannot be used to buy items such as alcohol, cigarettes, or foods that are hot at the point of sale (for example, rotisserie chicken or fast food).

- The United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) administers the program. However, the Kansas Department for Children and Families handles the day-to-day operations. This includes processing applications and distributing benefits.

- SNAP benefits are provided on an electronic benefit transfer (EBT) card that recipients can use at any participating business. Participating retailers include grocery stores, convenience stores, and some online businesses. EBT cards can only be used to purchase allowed food items and will automatically reject attempted purchases of prohibited items.

- The federal government funds the full cost of SNAP benefits. However, the state’s administrative costs are split evenly between the state and the federal government. Administrative costs can include costs such as verification efforts, informational activities, and application processing. In federal fiscal year 2025, the federal government spent about $403 million on SNAP benefits for Kansans. Additionally, Kansas and the federal government split about $30 million in administrative costs.

- In fiscal year 2025, about 188,000 Kansans received SNAP benefits each month.

Individuals must submit an application and provide extensive financial and other information to the Department for Children and Families (DCF) to qualify for SNAP benefits.

- To qualify for SNAP benefits, an individual must submit an application to DCF. The application can be completed online or on paper. The application is also used to determine if an individual is eligible for the Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) program and childcare assistance.

- Applicants must provide a variety of non-financial information to ensure they qualify. This includes information such as a social security number, marital status, and criminal history. Generally, the applicant only needs to provide the information on the application (i.e. name, address, marital status). However, the applicant may need to submit supporting documentation for some non-financial information. For example, DCF may request proof of citizenship.

- The application also requires extensive financial information. Generally, applicants only need to provide the information requested on the application. However, DCF may ask for supporting documentation including bank statements, income tax returns, or proof of medical bills. The financial information requested on the application includes 3 broad types of information:

- Income information which includes wages, social security income, child support, and alimony.

- Other resources such as savings, vehicles, or property.

- Expenses such as rent or mortgage payments, medical expenses, and utility costs.

- Most applicants must meet 2 financial criteria to qualify for SNAP benefits. However, households with an elderly or disabled member only need to meet the net monthly income test.

- The applicant’s gross monthly income must be at or below 130% of the federal poverty level. This is determined by totaling the applicant’s total income for the month. In 2025, this threshold was $3,380 per month for a family of 4 ($40,560 annually).

- The applicant’s net monthly income must be at or below 100% of the federal poverty line. This is determined by deducting various expenses (for example, mortgage or rent payments, utilities, and childcare costs) from the applicant’s income. In 2025, this threshold was $2,600 per month for a family of 4 ($31,200 annually).

- The amount of the benefit is based on the size of the household and the household’s net monthly income. A household is anyone (including children) who live in the same house and customarily purchase or prepare food together. The more income the household has the less it will receive in SNAP benefits. If the household does not have any income, it receives the maximum benefit for the size of the household. In 2025, the average benefit was about $360 per household per month.

- SNAP recipients are required to provide certain updated information periodically to ensure they are still eligible for benefits. Recipients must report several changes that could affect their eligibility. For example, households must report changes in wages or the number of hours worked. Additionally, most SNAP recipients must certify annually that they still qualify for the benefit. This process requires an interview and verifying that certain financial and household information are still correct.

DCF takes several steps to process and verify each application.

- Federal laws and regulations require DCF to take certain steps to verify each application. Federal law requires DCF to verify certain information the applicant provided with agencies such as the IRS, Social Security Administration, and the Kansas Department of Labor. This includes information such as the applicant’s social security number and certain wage information. DCF is also required to participate in the USDA’s National Accuracy Clearinghouse (Kansas is scheduled to start participating in February 2026). The Clearinghouse verifies that applicants are not already receiving SNAP benefits in another state.

- DCF uses a simplified eligibility system by which the department generally accepts what the applicant reports on the application. However, DCF also uses a “prudent person” standard to determine if they should request documentation. Except for the information the federal government requires DCF to verify, DCF will request documents only if a “prudent person” would find the information questionable or inconsistent. Examples include an individual who has a history of providing conflicting information or seems to have a higher standard of living than their reported income would permit.

- DCF takes many steps to process and verify information provided on each application:

- DCF staff manually enter paper applications into the Kansas Eligibility Enforcement System (KEES). Online applications are automatically added. All applications are assigned a case number. Staff determine whether the application should be expedited (which makes benefits available in 7 days) or be reviewed in the standard way (which makes benefits available in 30 days). An application may be expedited for multiple reasons. For example, an application can be expedited if a household has monthly income of less than $150 and other resources that are less than $100.

- DCF staff conduct a mandatory interview (by phone or in person) with the applicant. During the interview, staff review the application for completeness. Staff use a standardized script to ensure all aspects of the application are consistently reviewed. Using the “prudent person” standard, staff may ask for verification documents to confirm any inconsistent or questionable information provided on the application. For example, staff may request information on household members or certain expenses.

- Staff review any documents and verify certain information that the federal government requires DCF to verify. For example, DCF staff verify social security numbers with the Social Security Administration and verify work information with the Kansas Department of Labor. Staff input the relevant information into KEES and KEES determines whether the applicant is eligible for benefits. If they are, KEES also automatically calculates the amount of monthly SNAP benefit.

- In 2025, DCF had 193 fully-trained staff to process applications and complete eligibility verifications for SNAP, TANF, and childcare assistance.

Payment Error Rates

The SNAP benefit eligibility determination is complex, and errors can occur at many points.

- DCF staff can make errors at many points while processing and verifying a SNAP application.

- Some applications are submitted on paper which require hand entering information into KEES. This creates opportunities for mistakes such as transposing numbers.

- The number of rules or circumstances that must be considered is significant. The manual that provides policies and rules to DCF staff who are processing and verifying SNAP applications is nearly 700 pages long. DCF also provides several other matrices, scripts, and guides that all contain additional information that must be considered. Every rule that must be applied creates an opportunity for an error.

- Additionally, some of the eligibility rules are complicated. For example, if an applicant shares expenses with a non-household member, then only a certain amount of those expenses can be deducted. If the portion of the expense attributed to the applicant cannot be differentiated from the non-household member, then the expense must be prorated in a specific way. Only that prorated amount can be deducted. The more complex and nuanced the rules, the more likely errors are to occur.

- Applicants can also make mistakes. The SNAP application includes TANF and childcare assistance, so it is quite lengthy (36 pages with over 200 questions). Applicants can transpose numbers or misunderstand questions and provide the wrong information. For those whose primary language is not English, an interpreter can be provided but language barriers also create opportunities for errors.

- It is important to note that not all errors are fraud. Fraud requires deliberately misrepresenting, concealing, or omitting information to gain a benefit. Although some applicants may knowingly falsify their information, it’s also likely that genuine human error occurs during the application process. Basic human error is typically not considered fraud.

The federal government monitors states’ SNAP benefit payments to ensure accuracy.

- The federal government monitors states on multiple metrics to ensure accurate payments, timely application processing, and appropriate access to SNAP. For the purposes of this audit, we are focusing only on the accuracy of the payments.

- The payment error rate provides a measure of the state’s accuracy in determining benefit amounts. Determining this measure consists of 3 broad steps:

- Each month, DCF selects a representative and random sample of monthly payments for review (about 90 payments monthly). Then a DCF quality control reviewer checks the accuracy of the payment determination. Federal rules prohibit this reviewer from having any previous participation in the sample cases. The reviewer reviews supporting documents and interviews household members or others to determine whether the recipient reported accurately and whether DCF staff made the correct decisions. Each month’s review must be submitted to the USDA. DCF’s sample must include at least 1,020 payments annually.

- If the quality control reviewer finds errors, DCF must notify the applicant and correct the benefit amount. If DCF made an overpayment, they typically subtract a portion of the recipient’s benefit going forward until the overpayment is paid back. If the quality control reviewer determines that the recipient should not have received SNAP benefits at all, the individual must pay back the money. If DCF made an underpayment, they increase the payment until the recipient has received the correct amount.

- USDA reviews a sample of the cases DCF reviewed to verify the accuracy of the state’s findings.

- The payment error rate for the state is calculated by dividing the total value of certain over-and under-payments by the total value of SNAP benefits in the sample for that time period.

- The payment error rate only includes errors above a certain dollar value. That value was $54 in 2023 and $56 in 2024. This means if the error resulted in an over or underpayment equal to or less than that set value, it is not included in the federal payment error rate calculation.

- The federal government has set a payment error rate tolerance threshold of 6%. A payment error rate greater than 6% indicates that the total dollar value of the errors (above the set threshold) exceeded 6% of the total SNAP benefits distributed that year.

- States are required to implement a corrective action plan if their annual payment error rate is 6% or greater. This plan requires the state to identify root causes for the errors and create a plan to address them. If the error rate exceeds 105% of the national average in 2 consecutive years, the federal government can assess a financial penalty. This has not happened in Kansas.

DCF’s SNAP payment error rate has exceeded the federal payment error rate threshold of 6% since 2019.

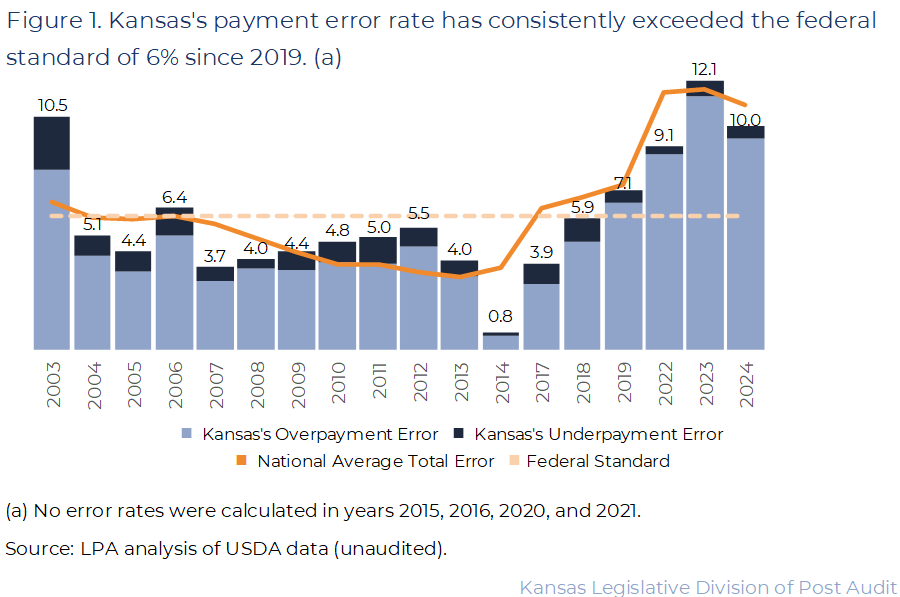

- We looked at the payment error rate for each year for the last 20 years. Generally, the error rate is calculated annually with some exceptions. In 2015 and 2016 the federal government did not release national error rates due to widespread concerns about the quality of the data states submitted. Additionally, the USDA suspended the requirement in 2020 and 2021 due to the pandemic’s impact on state operations and workloads.

- Figure 1 shows Kansas’s payment error rate each year since 2003. As the figure shows, Kansas’s payment error rate has exceeded the federal tolerance threshold of 6% since 2019. Further, it has significantly exceeded that threshold since 2022. It reached its highest level in 20 years in 2023 when it reached 12%.

- The overpayment errors are consistently significantly greater than the underpayment errors. For example, in 2024, the overall payment error rate was about 10%. Of that, the overpayment error rate was 9.4% compared to the underpayment rate of 0.55%.

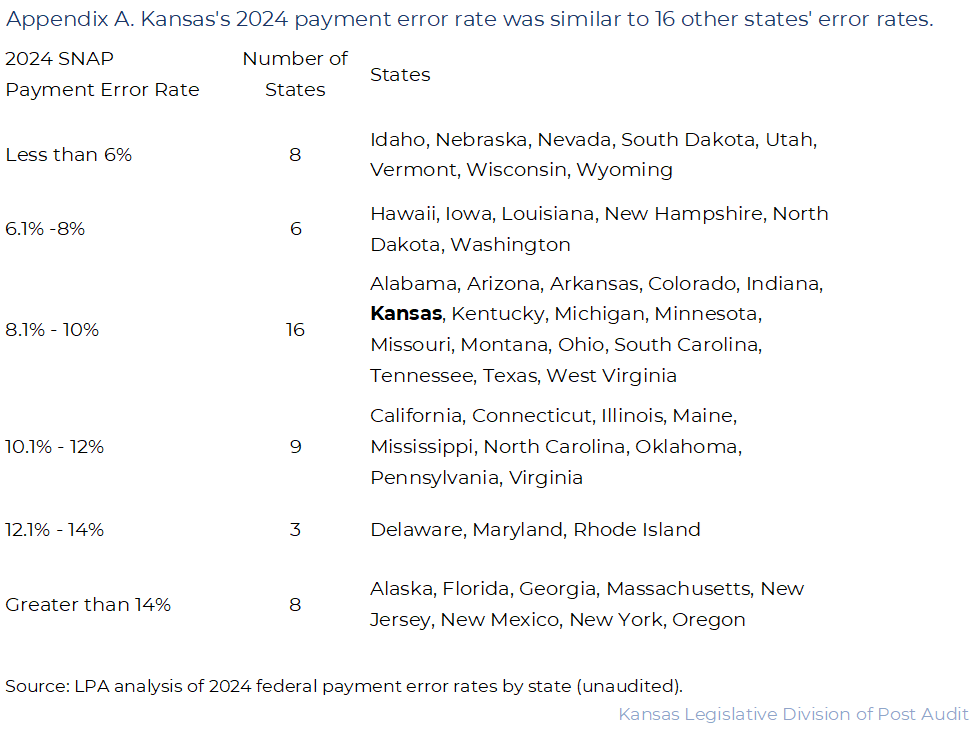

- Kansas’s payment error rate was slightly less than the national average in 2024. In that year, the national payment error rate was 10.9%. Kansas’s rate was 10%. However, Kansas’s rate is slightly higher than its 4 neighboring states which had an average error rate of 8.9%. Last, in 2024 only 8 states had a payment error rate equal to or less than the federal threshold of 6%. Appendix A provides additional information on the 2024 SNAP payment error rate by state.

- Because Kansas’s error rate has exceeded the federal threshold, the USDA required DCF to create a corrective action plan. The purpose of the plan is for the state to describe how it will address the high error rate. DCF’s current plan includes increasing staff training, clarifying information in user manuals, and utilizing additional technology. While the plan is in place, DCF must provide updates to USDA twice a year. The USDA will determine when DCF has adequately implemented the corrective actions and declare the plan closed. As of the writing of this report, the USDA has not yet closed DCF’s most recent corrective action plan.

In the 2 years we reviewed, most of the nearly 300 errors that contributed to the payment error rate were related to miscalculating an applicant’s income and resources.

- Due to federal laws that prevent DCF from providing SNAP applications to us, we were unable to directly review SNAP applications. As a result, we had to rely on documentation provided by DCF that notes the types of errors and the primary cause of those errors as they determined them. We reviewed the 2,165 payments that DCF selected as their payment error rate sample for fiscal years 2023 and 2024. Out of those cases, 286 had errors large enough to include in the federal payment error rate calculation.

- As part of DCF’s review, they determine whether the error was primarily due to recipient or DCF error. According to DCF’s review:

- Across the 2 years, DCF attributed about half of the errors to DCF staff errors. However, the percentage was slightly higher in 2023 (51% in 2023 vs. 45% in 2024). This includes errors such as staff incorrectly prorating benefits, allowing ineligible expenses, and failing to update income.

- DCF attributed the other half of the errors to recipients. This included information related to items DCF may not have verified in their review of individuals’ applications. For example, we saw some payments where an individual did not report the number of household members accurately, did not report they were receiving benefits in other states, or misreported expenses.

- We categorized the payment errors by type based on DCF’s description of the error. In some cases, we identified multiple errors within the same payment. Recipient errors and DCF staff errors contributed to each of the 3 types of errors.

- An income and resource error is related to an incorrect determination of the income or resources that an applicant has. This could occur because DCF misapplied a rule or because an applicant provided incorrect information. For example, if an applicant fails to report they receive child support payments, this would be considered an income and resource error.

- An allowed expense error is related to an incorrect determination of the applicant’s household, childcare, or medical expenses. For example, if DCF staff included a utility deduction that the applicant did not qualify for, this would be considered an expense error. To qualify for SNAP, an applicant must have net monthly income below a certain threshold. Net monthly income is determined by subtracting certain allowable expenses from the applicant’s income. As a result, it is important that expenses are calculated correctly to accurately determine what the household’s monthly payment should be.

- A non-financial error involves an error that is unrelated to any of the financial information an applicant must provide. Typically, it involves misreporting the number of people who live in the household or the citizenship status of those household members. For example, an applicant who reports there are 4 people who live in the household when there really are only 3.

- Across the 2 years, most of the errors were related to mistakes in the calculation of an applicant’s income and resources. These numbers do not add up to 100% because about 30 payments had multiple errors.

- 59% (170) of the payments had at least 1 error related to the recipient’s income and resources. Some of these errors included recipients who did not report all their wages or social security income. This category also included errors DCF staff made. For example, we saw cases where DCF did not properly include child support payments or social security income.

- 33% (95) of the payments had at least 1 error related to an allowed expense. This includes applicants who did not accurately report expenses such as childcare expenses or rent. We also saw errors in which DCF staff misapplied utility expense allowances or did not properly include medical expenses.

- 17% (50) of the payments had at least 1 non-financial error. For example, we saw a student who was incorrectly reported as part of the household, a non-citizen who was granted benefits, and an incomplete application that DCF accepted.

- Across the 2 years, about 84% (241) of the errors resulted in overpayments to SNAP recipients. This included 113 payments to households that did not qualify for SNAP benefits at all. The other 16% (45) were underpayments. The average overpayment was $292 per month while the average underpayment was $111 per month.

Staff turnover, the complexity of SNAP eligibility rules, and inconsistent verification efforts appear to be significant factors in the department’s SNAP payment errors.

- We reviewed DCF’s payment error documentation and talked with DCF officials about the root causes of the department’s error rates. Because we are not authorized to review the applications, we were unable to determine the specific reasons for the errors. Thus, we had to rely on DCF’s documentation. As a result, we could only determine the root causes of the errors at a high level. However, a few factors appeared to be important:

- DCF officials told us that recent turnover rates among the staff who process applications has been about 30%. Additionally, they told us that it takes about a year for staff to be fully trained in processing and verifying applications. Significant turnover leads to a consistent influx of new people who may not yet have the necessary experience to accurately process applications.

- The rules that determine SNAP eligibility and the proper payment amounts are nuanced and complex. For example, each SNAP household is allowed 1 vehicle per adult household member as an excluded resource. If an adult has more than 1 vehicle, that vehicle can also be an excluded resource but only if it is used to transport a disabled household member or used to earn income. If a vehicle is not exempt, then DCF staff must determine fair market value and then count that towards the allowed resource amount. Additionally, staff must know the rules for additional programs like TANF and childcare assistance. This increases the complexity of making sure the correct rules and criteria are applied for SNAP.

- DCF uses a “prudent person” standard to determine what information may be questionable which appears to cause some inconsistency. Kansas uses a simplified eligibility determination in which DCF generally accepts the individual statement as the basis of eligibility. Federal rules require some application information to be verified (i.e. identity, citizenship, and income) but many factors are only verified if a “prudent person” would find them questionable or inconsistent with other information on the application. This is a somewhat vague standard and appears to have created some inconsistency in what is verified and how far staff go to verify questionable information.

- The DCF quality control reviewers appear to dig deeper into verification and thus find more inconsistencies in what applicants report. The quality control reviewers have fewer applications to review than the staff who initially process applications. Additionally, they do not have the same time limits. They appear to often dig deeper into the application and verify more information through documents and interviews. As a result, they find more errors in the information that applicants provide than the original staff who processed the application. Additionally, the reviewer double checks the accuracy of the original DCF decisions. Sometimes the reviewer finds that staff applied the wrong rule or that certain income or expenses were not considered.

DCF told us modifications to KEES might reduce SNAP payment errors but it’s unclear how much impact additional actions might have.

- DCF officials told us that 2 modifications to KEES would likely help reduce errors. DCF has not implemented these features because of a lack of funding to do so.

- First, they told us a chatbot assistant that would quickly provide the rules to the staff as they are processing the application would likely reduce errors. For example, it could provide the specific rule for the circumstances under which utility expenses must be verified and what type of verification is acceptable. The KEES user manual is just over 1,700 pages long. Further, the manual that covers the specific rules for SNAP is nearly 700 pages and also includes rules for TANF, and childcare assistance. A more automated way to find the proper rule to apply may be helpful.

- Second, they told us a document processing feature that would scan applicant documents and automatically populate the proper field would likely reduce errors. DCF officials told us this would reduce the number of data entry errors and it also would save staff time.

- If DCF had more experienced staff, it may also reduce payment errors because experienced staff would be better equipped to navigate the program’s complex rules. However, retaining more staff and reducing turnover typically requires many actions including increasing pay. It was unclear to us what caused DCF’s high turnover rates. As such, it is unlikely that any recommendation we make would adequately address this issue.

- If DCF staff verified more information on SNAP applications, it may also reduce payment errors. However, it’s not clear how much more verification DCF staff would need to complete to meaningfully improve the payment error rate. Because we could not review applications, we were unable to determine more specific trends in errors. As a result, we cannot point to which information should be more consistently verified or what impact that might have on the error rate.

- DCF must balance accuracy with providing service to a vulnerable population. The more documentation the department requires for verification, the more potential obstacles exist for individuals to access the program. Additionally, more verification requires more time for applications to be approved. These are tradeoffs that DCF officials must weigh when considering how to manage the SNAP program. We were not in a position to recommend to DCF how best to balance these competing issues.

Other Findings

Across the 2 years we reviewed, we identified several hundred additional errors that were not included in the federal payment error rate because the dollar value of the error was less than the federal reporting threshold.

- By federal rule only errors that exceed a specific dollar value are counted in the payment error rate. That value was $54 in 2023 and $56 in 2024. This means errors that resulted in over or underpayments less than the federal threshold are not included in the payment error rate.

- We reviewed all the errors DCF identified, including the ones not reported as part of the federal payment error rate. Across the 2 years we reviewed (2023 and 2024), DCF reviewed 2,165 payments and identified errors with 970 of them (45%). 286 of the errors exceeded the federal threshold and DCF included them in the payment error rate. The remaining 684 payment errors were less than the federal threshold so DCF did not calculate them in the error rate. About half of the unreported errors had a dollar value of $15 or less per month.

- These unreported errors were similar to the errors that DCF reported as part of the payment error rate. For example, most of the errors were related to mistakes in income and resources (63%) while a much smaller percentage were related to non-financial errors (2%).

Changes in federal law could result in the state paying for a larger share of SNAP costs.

- In 2025, Congress passed the One Big Beautiful Bill Act which imposes cost sharing penalties on states whose payment error rate is equal to or greater than 6%. States with a payment error rate of:

- at least 6% but less than 8% must contribute 5% of the total SNAP benefit costs.

- at least 8% but less than 10% must contribute 10% of the total SNAP benefit costs.

- 10% or greater must contribute 15% of the total SNAP benefit costs.

- If the payment error rate remains at the levels of the last few years, the state will be responsible for paying 10% to 15% of SNAP costs. Total SNAP benefit costs in 2024 were a little over $400 million so this could be about $40 to $60 million in state funding.

- Regardless of the state’s payment error rate, starting in fiscal year 2027, the federal government will fund 25% of the state’s administrative costs rather than 50%. This will likely increase Kansas’s administrative share of SNAP costs by $15 to $20 million.

Conclusion

The state’s SNAP payment error rate has significantly increased since 2017 and has exceeded the federal error threshold (6%) since 2019. In the last two years, the errors were related to a combination of mistakes made by applicants and mistakes made by DCF staff. The quality control process is meant to uncover and correct these errors. However, the root causes of the errors appear to be related to a few issues. The complexity of the SNAP program rules, DCF staff turnover, and inconsistent verification efforts all contributed to the state’s payment error rate. Kansas does not appear to be alone with these issues. As of 2024, only 8 states had payment error rates at or below the federal threshold. This suggests that other states may face some of the same challenges as Kansas when it comes to correctly determining SNAP eligibility and benefits.

Recommendations

- Department for Children and Families officials should pursue funding opportunities for the 2 additional KEES modules discussed earlier in the report.

- Agency Response:

- DCF is requesting funding during FY 26 $2,797,302 AF / $1,398,651 SGF and FY27 $1,613,960 AF / $968,660 SGF for Payment Error Rate Reduction Tools. The Governor’s Budget Recommendations for FY 26 and FY 27 include this funding. This includes both KEES modules recommended by Legislative Post Audit at $1,408,960 in FY 2027.

Agency Response

On January 6, 2026 we provided the draft audit report to the Department for Children and Families.

Its response is below. Agency officials generally agreed with our findings, conclusions, and recommendations.

DCF Response

Thank you for the opportunity to provide a response to the Performance Audit Report: Reviewing Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program Payment Error Rates and Benefit Card Transactions, Part 1 (January 2026). We appreciated the professional conduct of the LPA staff during the course of the review. The Kansas Department for Children and Families (DCF) respectfully submit the following responses for the audit findings listed below.

Department for Children and Families officials should pursue funding opportunities for the 2 additional KEES modules discussed earlier in the reports.

DCF is working aggressively to reduce the Payment Error Rate (PER) through an improvement plan. The PER for FFY 2025 through August 2025 was 9.13%, and the PER for August 2025 – the most recent case review month available – was 5.50%.

As the agency has worked closely with FNS on an improvement plan to minimize errors through technical assistance, training for case workers, improving data systems, and implementing new policies and procedures. The plan includes policy and process changes such as verifying shelter costs, upgrading the supervisor case review system, and increasing staff training.

DCF has also been working with the consulting group, Human Services Group, since October 2025 on a rigorous assessment to identify gaps, determine steps to improve case reviews and monitoring, as well as identify opportunities for system changes (requested in the supplemental and enhancement budget requests).

Long-term planning includes the technology supports recommended by the auditors that create efficiencies and improve quality control detection. These supports will help sustain performance with federal threshold requirements and were included in the Governor’s Budget Recommendations.

DCF is requesting funding during FY 26 $2,797,302 AF / $1,398,651 SGF and FY27 $1,613,960 AF / $968,660 SGF for Payment Error Rate Reduction Tools. The Governor’s Budget Recommendations for FY 26 and FY 27 include this funding. This includes both KEES modules recommended by Legislative Post Audit at $1,408,960 in FY 2027.

The first PER reduction technology tool is a chatbot assistant. This technology would quickly provide the rules to the staff as they are processing the SNAP Food Assistance applications. For example, the chatbot would quickly identify the specific rule under which utility expenses must be verified and what type of verification is acceptable. The KEES user manual is more than 1,700 pages long. Further, the SNAP Food Assistance manual is nearly 700 pages and also includes rules for TANF and Child Care Assistance. A more automated way to find the proper rule to apply would be an effective use of resources and extremely productive for eligibility staff. This change independently would cost the agency $780,000 FY26/$30,000 FY27.

The second is a document processing feature that would scan applicant documents and automatically populate the proper field, likely reducing errors. This would specifically reduce the number of data entry errors, and it also would save staff time. This change is a part of the KEES system changes for FY27 $1.4M All Funds.

Conclusion

We thank the Legislative Post Audit team for the opportunity to discuss the SNAP Payment Error Rates. As stated in the report’s conclusion, the complexity of the SNAP program rules, staff turnover and inconsistent verification efforts have contributed to the Payment Error Rate. As an agency we have been leveraging all tools to reduce the payment error rate and will continue to do so. Thank you for the opportunity to provide clarification and response.

Sincerely,

Laura Howard,

Secretary

Patrick M. Roche

Patrick Roche,

Audit Services Director

Appendix A – 2024 State Payment Error Rates

This appendix shows the payment error rate range for each state in 2024.