2-Year Summary of Security Controls in Selected State and Local Entities (2024-2025)

Introduction

K.S.A. 46-1135 authorizes our office to conduct information technology audits as directed by the Legislative Post Audit Committee through an annual approval process. We issued individual reports to each agency in both 2024 and 2025. These reports are confidential under K.S.A. 45-221 (a)(12) & (45) because releasing that information could jeopardize the entities’ IT security.

We periodically publish summary reports on our IT security work to keep the public informed while protecting individual sensitive entity findings. This is the 4th public summary report and answers the following question:

Do state and local entities adequately comply with significant information technology security standards and best practices?

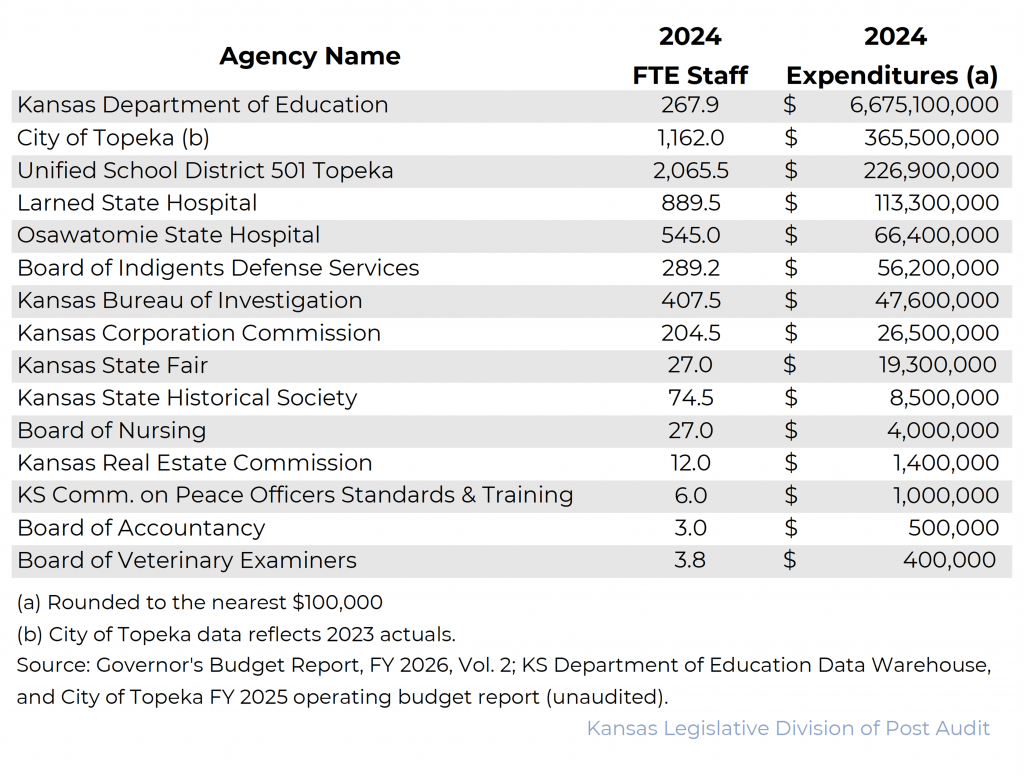

Between January 2024 and December 2025, we conducted 15 IT security audits of 13 state agencies, one school district, and one city. Appendix A lists the 15 entities, their expenditures, and their FTE.

Our audit work generally evaluated 10 IT security control areas. Within each area, we measured an entity’s compliance based on selected security standards. Those standards are codified in Information Technology Executive Council (ITEC) policies and state law. We also reviewed compliance with certain best practices. We did this because the state’s standards had not been updated to include certain accepted industry standards. We reviewed nearly 50 applicable control items across audited entities.

To assess compliance, we interviewed staff, reviewed relevant policies and procedures, and evaluated relevant computer settings. We reviewed security awareness training documentation and other security controls. We used entity staffing information to evaluate certain deprovisioning, asset inventory, and account control processes. We also inspected data centers and performed or reviewed vulnerability scans on entities’ computers. Lastly, we conducted or evaluated limited social engineering tests.

This report provides insight into the 15 individual and confidential IT audits conducted in 2024 and 2025 by summarizing key findings. Because this report represents a summary of underlying audits, it was not conducted in accordance with generally accepted government auditing standards.

Specific caveats follow:

- For each entity’s audit, we limited our work to a handful of controls within each area in our audit plan. Because we did not evaluate a larger number of controls in areas such as boundary protection, access control, or system controls, there is residual risk that additional control weaknesses may exist.

- Sometimes we relied on the entity, the Office of Information Technology Services (OITS), or the Kansas Information Security Office (KISO) to provide certain data, including security awareness training records, phishing test results, and vulnerability scanning reports. We conducted testing on these data sets to consider the source data sufficiently reliable for our analyses.

- Some work required the use of samples. In some cases, we used judgmental selections. Although these results cannot be projected, any identified problem findings represented security threats which in and of themselves provided us with reasonable assurance that a problem existed. It is possible our work using samples showed compliance despite existing problems. As a result, our work should be viewed as an indicator of an area’s status and not viewed as absolute assurance.

Almost half of the 15 entities we audited in 2024 and 2025 did not substantially comply with applicable IT security standards and best practices.

Responsibilities and Initiatives

Under established security standards, state and local entities must protect sensitive information against data loss or theft.

- Many Kansas agencies collect sensitive personal information on taxpayers and citizens. Examples include student records, tax returns, criminal records, and health care information. Loss or disclosure of this information can have significant consequences.

- Kansans use state agency services and programs and depend on agencies to protect their personal information.

- Government agencies across the nation are consistently targeted because they maintain valuable information. Here are several examples of local security incidents that have happened since January 2024:

- In March 2025, Atchison County shut down their offices to respond to a cyber incident. The Atchison County Offices were closed to the public for multiple days, impacting services across the county. Newspaper articles stated fire and emergency resources continued to operate. The county hired cybersecurity and data forensics consultants to investigate and assist with restoring services. In November, the Atchison Sheriff’s Office announced that the “CodeRED” alert system, which provides enrolled residents with alerts to weather and life safety warnings, was affected. Reportedly, the legacy system was damaged, and its data was taken. The county was planning to create a new platform. The specific cause of the incident has not been publicly disclosed.

- In May 2024, the City of Wichita suffered a cyberattack. Criminals accessed the law enforcement data system, which maintained 77,000 cases at the time of the attack. Authorities did not know how many cases were accessed. In response to the attack, Wichita shut off network access to all systems, leaving some systems down for weeks. A Russian cybercriminal group known as LockBit took credit for the attack, but the city did not publicly confirm this.

- In April 2024, a bi-state initiative between the Kansas and Missouri Departments of Transportation, known as KC Scout, suffered a ransomware attack. This breach crippled the website, cameras, and message boards for months. KC Scout is a system designed to lessen traffic jams and improve emergency response to traffic situations.

- In January 2024, a ransomware attack targeted the Kansas City Area Transportation Authority (KCATA), which is a bi-state agency jointly operated by Kansas and Missouri. KCATA alerted authorities, including the FBI, to inform them of the attack. The incident left regional RideKC call centers unable to receive calls from customers. Buses remained operational.

State and local entities must balance their business needs against security risks.

- Generally, state agencies are not in the information security business. Their focus is on accomplishing their core missions such as collecting taxes, housing inmates, monitoring air and water quality, and so on. Similarly, Kansas school districts’ missions center on educating children from kindergarten through 12th grade.

- Implementing security controls takes staff, time, and resources. Security controls often can reduce staff speed or limit functionality. This creates tension between business needs and security risks.

- Entities must understand and evaluate their security risks to make informed decisions about which controls to put in place and how to go about it, all while carrying out their primary missions.

Several statewide initiatives are aimed at improving the state’s information security.

- The Kansas legislature created the Information Technology Executive Council (ITEC) in 1998. ITEC has established security policies all state agencies must follow.

- The state’s ITEC security policies are like other security standards, including those issued by the Center for Internet Security (CIS) and the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST). The state’s standards require policies and procedures over physical controls, system controls, and application controls. Together they form a multi-layered approach to safeguard confidential data and are designed to help agencies create and maintain a strong security posture.

- In 2011, Governor Brownback initiated IT centralization through Executive Order 11-46. This order required all non-regent IT directors under the Governor’s jurisdiction to report to the Executive Chief Information Officer. It was intended to increase the efficiency and uniformity of IT within the executive branch.

- The 2018 Cybersecurity Act (K.S.A. 75-7236 et seq.) aimed to reduce the risk of cybersecurity breaches within state agencies. The 2023 and 2024 Legislatures further amended or codified IT and cybersecurity-related processes for state agencies. Important statutory provisions from the Cybersecurity Act and subsequent revisions are as follows:

- The Act pertains to most executive branch agencies with a few exceptions. The 2018 Act exempted elected office agencies, the Adjutant General’s department, the Kansas Public Employees Retirement System, the regents’ institutions, and the Board of Regents. The 2024 Legislature required the judicial and legislative branch agencies, as well as elected offices, to appoint a Chief Information Security Officer (CISO) for their respective branch, office or agency. The amendment also required each CISO to establish security standards and policies to safeguard respective IT systems and infrastructure.

- The Act created the Kansas Information Security Office (KISO) as a separate state agency to administer the Act. KISO is led by the executive-branch Information Security Officer. The 2024 amendment required the CISO to develop a cybersecurity program for executive branch agencies to comply with that’s based on the federal National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) framework. KISO also ensures cybersecurity awareness training is available to all branches of state government.

- The Act clarified that agency heads remain responsible for their agency’s security postures. K.S.A. 75-7240 clarified that agency heads have several specific responsibilities, including designating an information security officer for their agency. Agency heads also were required to participate in certain security initiatives and services, and to notify the CISO about breaches within 12 hours after discovery. 2023 amendments added reporting responsibilities for significant security incidents by government contractors or any public entity to the Kansas Information Security Office.

- The 2024 Legislature added the possibility of financial penalties for state agencies not reaching certain security levels. The 2024 House Sub. for Senate Bill 291 included a requirement for agencies to reach certain security levels within the NIST cybersecurity framework. Specifically, all state agencies need be at Level 3 “repeatable” by July 1, 2028, and at Level 4 “adaptive” by July 1, 2030, under this framework. Agencies not reaching these levels could be subject to 5% budget cuts. The law required respective CISOs to coordinate with the U.S. Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency to conduct audits to determine entities’ security levels. These amendments had a sunset provision as of July 1, 2026. That’s because legislators remained concerned about these requirements.

IT Security Audit Method

- At the start of each calendar year, the Legislative Post Audit Committee approved our suggested auditees. We selected agencies based on past audit results, the length of time that had passed since their last IT security audit, and other criteria. In 2024, we added a K-12 school district (USD 501-Topeka) to our list of auditees, which the Committee approved. For 2025, we deliberately focused on smaller agencies, several of which had never received an IT security audit from us previously. The Committee also authorized us to audit one of several larger cities we suggested evaluating in 2025. We selected the City of Topeka.

- It should be noted that the state standards we used (based on ITEC requirements or law) do not apply to Kansas school districts or cities. However, because neither the school district nor the city we audited had specific security standards they followed, we applied our audit plan as a best practice standard for those auditees.

- We generally evaluated roughly 50 individual control items across 10 areas. These areas included traditional cybersecurity risk areas, such as security awareness training, account security, and vulnerability remediation. At many entities, we also evaluated controls for a selected IT system. Most individual control items we evaluated came from ITEC policies or state statute. Lastly, our audit plan included a handful of best practices that were not codified in Kansas policy or law.

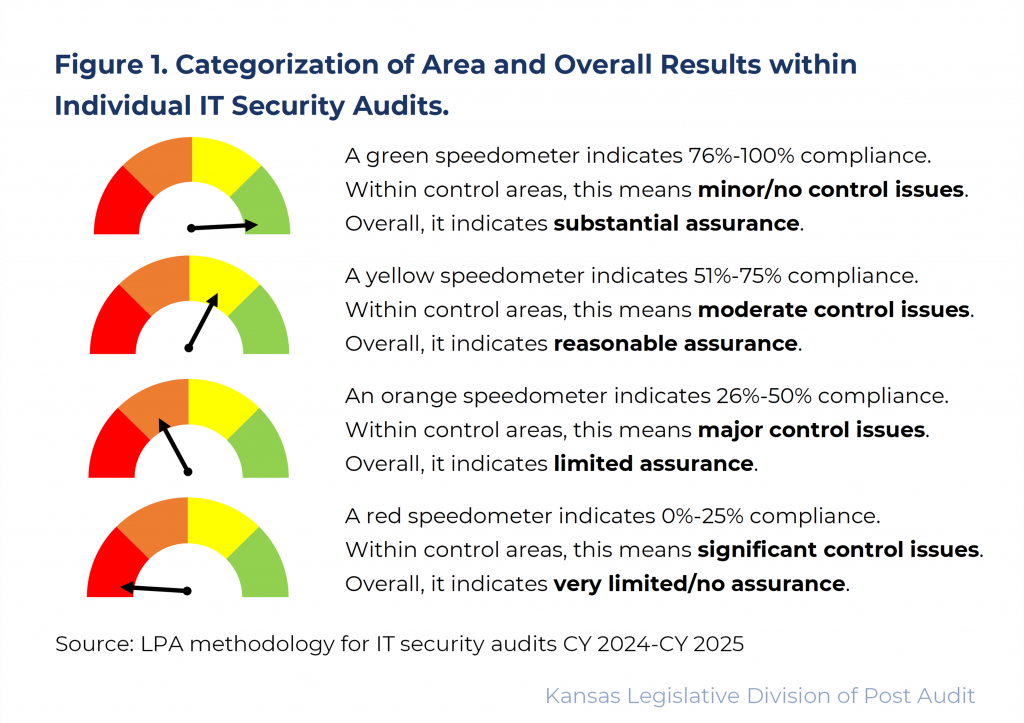

- To score entities’ performance within each control area, we awarded between 0 and 3 points for each requirement or best practice we evaluated. Generally, we awarded 3 points for full compliance and 2 points when the entity was mostly compliant. We awarded 1 point when the entity had taken initial steps towards compliance and 0 points if the entity had no process in place to adhere to the requirement. The resulting points in each control area were converted to a percentage which fell into 1 of 4 possible quadrants. Figure 1 shows the possible results.

- Lastly, we assessed overall performance for each auditee using the results from all areas and opined on root causes for entities’ respective security postures within each confidential report.

IT Security Audit Results

7 of the 15 entities audited in the past 2 years did not substantively comply with applicable IT security standards and best practices.

- We tested between 36 and 47 control items across 8 to 10 areas, generally averaging 43 items per audit.

- All entities had at least some control issues, ranging from a low of 15 to a high of 42 items with less than full compliance. In other words, no entity passed with a clean review.

- 7 entities scored below 50% and received an overall ‘limited’ or ‘very limited’ audit assurance rating. Such entities can be thought of as not substantively complying with applicable audit standards and best practices. These 7 entities generally also had significant or major control issues in 4 or more control areas. The other 8 audits we conducted resulted in ‘reasonable’ assurance’ (none reached substantial assurance).

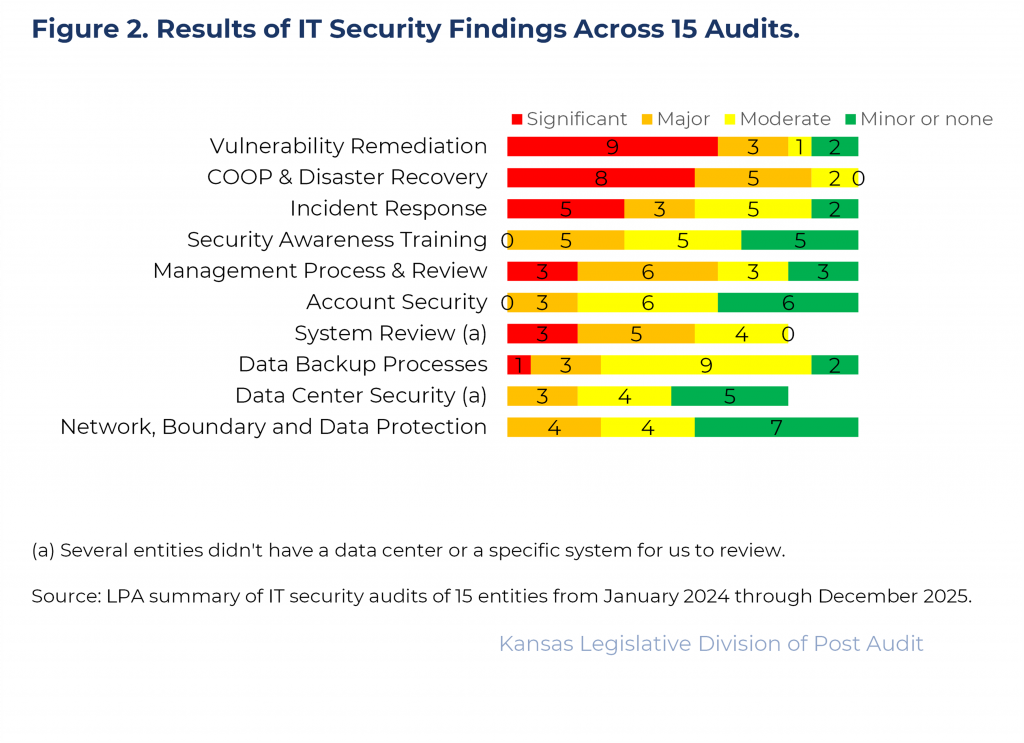

- Figure 2 shows the number of findings across all 15 audits by IT control area and severity.

- As the figure shows, a handful of areas had the most significant security weaknesses. Those areas included vulnerability remediation, continuity of operations/disaster recovery, and incident response.

- We also judgmentally selected and reviewed a specific IT system that maintained or processed confidential or sensitive data at most audited entities. This is shown in Figure 2 as “System Review.” Findings in this area are discussed in greater detail later in the report.

The security findings summarized in this report are similar to those in previous summary reports.

- Our audit work varies somewhat from year to year. Nevertheless, we consistently evaluate certain security areas we think are most important and part of a basic security process.

- State agencies and local entities continue to have similar IT security issues to those we’ve identified as far back as 2003. Results in this report summary (CY 24-25) were generally similar to the results from the 2 previous summary reports (CY 20-22 and CY 17-19). Areas of greatest concern continued to be inadequate scanning and patching processes, poor management processes, and system controls, and weak continuity of operations planning.

- In 2025, we focused exclusively on smaller state agencies. These agencies do not maintain the depth and breadth of confidential data as larger agencies such as the Department of Revenue or the Department of Health and Environment. However, they do maintain some confidential data and may connect to other state agencies which could present a threat surface.

- 7 of the 15 entities were audited for a second time over the past decade. Our audit program changes over time, and audits were between 5 and 10 years apart, making direct comparisons difficult. Nevertheless, we noted some entities had repeated findings, while another entity improved its security posture. For example:

- We found 1 entity had poor security processes in our prior audit and had repeat findings in vulnerability remediation, incident response, business contingency, and system-specific issues. Another entity’s security posture appeared to have slipped from our first audit to the second.

- Yet we saw 1 entity’s results improve because they had created processes to train its staff in security awareness and had developed incident response and continuity of operations plans that were lacking before.

Inadequate top management attention, lack of resources, and poor contractor administration generally were the main reasons for compliance problems.

- Top management ultimately is responsible for an entity’s information technology governance, risk management, and compliance. Despite this, we often found top management had not sufficiently prioritized IT security, set sufficient expectations, or provided sufficient oversight to ensure compliance with IT security standards. We also found several entities lacked strategic planning towards a stronger IT security culture, based on repeat audit findings . For several entities, we noted executive leadership had changed since our last audit, which may have contributed to less attention or stalled security initiatives.

- Inadequate IT security staff resources and expertise make it difficult to create or maintain a security baseline and retain institutional knowledge. Several entities had no or few security staff (including a dedicated Security Officer) to carry out IT security work despite these entities maintaining confidential data. In several entities, we noted IT security resources were likely insufficient given the entity’s size and federal compliance requirements. Conversely, entities with sufficient IT resources or experienced staff generally had a more robust security posture.

- We found some IT services that entities contracted for were not provided, not documented, or not properly monitored. Many of the 15 auditees relied on services from another state agency (Office of Information Technology Services, Kansas Information Security Office) or private contractors. In several audits, the parties lacked a formalized Memorandum of Understanding (MoU) or Service Level Agreement. Without such an agreement, it is difficult to know what each party is responsible for and to hold contractors accountable for their performance. This is especially important for small agencies that do not have the experience and manpower to stay on top of various security tasks. A couple of agencies had MoUs in place. However, there was confusion about who was accountable for security because the contracted Information Security Officer didn’t directly report to the agency director, as the law requires.

Most Significant or Most Common Security Weaknesses Across Entities

Most entities (80%) did not adequately scan or patch their computers to keep them secure.

- Over time, vulnerabilities in computer software are discovered that could allow someone to break in and harm an entity’s network or steal its data. Entities must periodically scan for known vulnerabilities. More importantly, entities must apply patches to keep their computers and their network secure.

- Without a systematic approach to identify and patch known vulnerabilities and eliminate unsupported products, entities leave their computers open to attack. This increases the risk those computers are used to compromise the entity’s network or even other entity systems.

- We evaluated entities’ computer scanning and patching processes and found:

- Most entities did not scan their computers at all or performed only partial or uncredentialed scans. At the time of our audits, 6 entities did not perform vulnerability scans at all and 3 entities did not scan all computers. Officials at 1 entity told us they didn’t have enough licenses to scan their entire network. Several entities could not provide documentation showing computers were scanned at least monthly as required. Lastly, a couple of entities appeared to run scans that were partially uncredentialed. Uncredentialed scans do not provide enough insight into computer vulnerabilities and can provide a false sense of security.

- Many entities did not adequately patch their computers. Scans generally measured entities’ computers based on the Common Vulnerability Scoring System (CVSS). The CVSS is a free and open industry standard to measure the severity of computer system vulnerabilities. For example, a CVSS score of 2 represents a low-level vulnerability, as classified by the industry. And CVSS scores of 7 or higher indicate a vulnerability is high or critical. We scanned a limited number of computers to evaluate entities’ existing vulnerabilities, with high average scores indicating poor patching processes. In several cases, we relied on OITS to provide scan results. For entities with findings in this area, our analyses (which excluded medium and low vulnerabilities) showed CVSS scores that generally ranged between 33 and 56 per machine. At 1 entity, the average CVSS score was 285 per computer (the scan included 9 computers). Such results indicated entities did not sufficiently patch serious software vulnerabilities.

- Most entities also used unsupported software, applications, or operating systems. When software products become too old to maintain, vendors no longer release security updates for them. Those products are considered “unsupported” and they represent permanent vulnerabilities for the entity using them. Our scans generally found unsupported versions of Microsoft software as well as unsupported 3rd party applications such as Adobe Acrobat or Flash Player, Apache, Oracle, and Mozilla Foundation. At 1 entity, we found unsupported operating systems such as Windows 7 (support ended early 2020) and Microsoft Server 2012 R2 (support ended October 2023).

- Companies like Microsoft, training organizations like SecureWorld, and federal agencies like CISA agree that unpatched vulnerabilities and unsupported software represent one of the largest risks to organizations.

Most entities (87%) did not have adequate continuity of operations and disaster recovery plans or did not appropriately test them.

- Continuity of Operations Plans (COOP) and disaster recovery plans outline an entity’s strategy to remain operational and minimize downtime of critical IT systems when faced with a major disruption. A Business Impact Analysis (BIA) is an important building block for disaster recovery plans because it requires entities to prioritize their IT systems based on mission-critical functions. Entities should review and update their plans periodically. Testing these plans periodically ensures that they work the way management intends and that important information has not been left out.

- Without adequate continuity of operations and disaster recovery plans, entities lack clear roadmaps for prioritizing and recovering IT systems after an emergency. This means entities may have to improvise when a disaster strikes, which can lead to confusion, duplicated efforts, and prolonged recovery times. When entities are unable to provide mission-essential services, it can erode public trust and cause reputational damage.

- We evaluated entities’ planning and testing controls for COOP and disaster recovery plans and found:

- Most entities had inadequate continuity of operations or disaster recovery plans. For instance, 3 entities’ COOP documents were not yet finalized or had expired. Additionally, we noted COOP documentation was not sufficiently updated at 9 entities: those plans listed staff that had since departed, included old system information, or were missing other required information. Lastly, 12 entities lacked a disaster recovery plan.

- Most entities had not conducted a business impact analysis, or their analyses were incomplete. BIAs should identify and prioritize entities’ IT systems and require entities to establish recovery time objectives (RTOs) and recovery point objectives (RPOs) for each system. The RTO defines how long critical systems can be down before they need to be back online. The RPO establishes how much data the entity can afford to lose, measured in time. 10 entities did not have a BIA at all. And 2 entities’ BIA documents did not include system level information or lacked RPO and RTO components.

- Most entities had not tested their continuity of operations plans within the past 2 years. One entity could not find records of testing. Another entity had documentation for a tornado or fire drills, which didn’t qualify for a full COOP test. Several other entities acknowledged not having done a tabletop or other test within 2 years prior to their audit.

- Results in this area surprised us given the Governor’s 2023 executive order. That order underscored the importance of creating and maintaining continuity of operations plans to state agencies.

More than half the entities (60%) had major or significant management process weaknesses.

- Entities should maintain up-to-date computer asset inventories. Another good practice is for IT contracts involving sensitive data to describe how confidential data is returned or destroyed when the contract ends. In addition, the 2018 Cybersecurity law required most executive-branch agencies to designate someone to oversee their security programs and for that Information Security Officer (ISO) to report directly to leadership (considered best practice for non-state agencies).

- We found entities had problems in all 3 areas.

- Most entities had asset inventories that were incomplete, had inaccuracies, or included outdated information. In some cases, problems were minor. In other cases, they were more substantial. For example, at 1 entity, the inventory lacked sufficient identifying information for about 14% of the roughly 360 computers. And 5 former employees still had computers assigned to them. We could not locate 4 of 20 judgmentally selected computers at that entity.

- We identified contract management issues at 2 entities. At both entities, at least 1 of the contracts we reviewed was missing clauses to ensure confidential data was returned or destroyed when the contract ended. We did not evaluate this item at all entities because some said they didn’t have relevant contracts.

- Nearly half of the entities did not designate an ISO to oversee their security programs. Surprisingly, this included both small and large entities. In some instances, designated ISOs did not report directly to executive leadership.

- Having a detailed, up-to-date computer inventory is the first step to understanding what needs to be monitored and protected within the network. A poorly maintained asset inventory increases the risk that computers may go missing without anyone noticing. When contracts lack proper data lifecycle steps, entities significantly increase their legal, financial, and reputational risks. When there is no designated ISO or if that staff doesn’t report directly to leadership, officials won’t get the information needed to make informed, risk-based improvements, and entities’ security posture will likely be weaker.

More than half of the entities (53%) had inadequate incident response plans or did not adequately test them.

- An incident response plan lays out steps to isolate, contain, and remedy a security incident. Security incidents can be minor (e.g. staff accidentally sending a client’s personal information to the wrong recipient) or major (e.g. network breach and subsequent ransomware). Security incidents should be defined and include both unintentional and intentional events to help individuals understand what situations should be reported. Entities should have processes to categorize incidents by severity and should establish a documented tracking process for incidents. Lastly, incident response plans should be tested to ensure they are up to date and work as intended.

- Having adequate plans and testing them regularly helps entities get through security breaches faster and more successfully. Without a proper IR plan, IT staff could miss important containment, recovery, or communication steps, resulting in prolonged or unknown issues, and avoidable financial penalties. Testing the plan is important because it allows entities to identify issues in a safe, controlled environment.

- Our review in this area identified the following:

- Several entities did not have incident response plans, and other entities’ plans were inadequate. At least 4 entities didn’t have a plan at all. More than half of the entities didn’t define security incidents for their users, or their definitions were incomplete (i.e. leaving out unintentional events). We noted other issues with the plans we reviewed, including 1 plan that included former staff. We also found several plans had incomplete, inconsistent, or no processes to categorize and track incidents. For example, 1 entity’s tracking process relied on ad hoc chat messages, but those messages weren’t retained more than 7 days. And 2 entities’ categorizations were for type of incident, not its severity.

- More than half of the entities had not tested their incident response plans or policies. We looked for classroom, tabletop exercises or live incidents in which incident response plans were being used. Of the 11 entities with incident response plans or policies, 8 didn’t have any documentation of a test or live incident that had been worked through.

- Incident response plans have become even more critical in recent years. That’s because Artificial Intelligence (AI) engines allow threat actors to create social engineering attacks (e.g. phishing, business email compromise) more easily and with more sophistication. This increases the risk that hacking attempts succeed, and entity networks and data are compromised.

Other Security Weaknesses Across Agencies

One-third of the entities (33%) did not provide adequate security awareness training.

- Security awareness training educates employees on why security controls are necessary and where risks come from. One of those risks is social engineering—the art of manipulating, influencing, or deceiving people to circumvent internal controls and gain control over computer systems. Security standards require training new staff within 90 days, and annual training for all users.

- Security awareness training processes were inadequate in a variety of ways. Several entities did not have formal policies or procedures or were missing key components in their training program. For several entities with new staff training processes, we noted problems with staff completing the training timely or at all. Several entities did not ensure employees consistently participated in annual training. Lastly, 8 entities exempted certain groups of employees – such as board members, unpaid interns, or staff without email accounts – from the training even though those users present an attack vector.

- Most entities failed various social engineering tests. We relied on the Office of Information Technology Services’ quarterly phishing campaigns or conducted our own tests at 13 entities. At the other 2 entities, we performed a clean desk review or a trash check. Of the entities that failed the phishing tests, click rates averaged 10.2%, and ranged between 3.2% and 25%. At 1 entity, the fail rate was 29%, after the agency removed the email filter to allow the phish email through. This shows how the risk to an entity increases when attacks get past technical defenses. The clean desk review revealed 2 offices with confirmed or suspected passwords in plain sight (from 16 judgmentally selected areas). We recovered documents with sensitive information from 5 shred or recycle bins out of 12 bins we judgmentally selected.

- Security awareness training is important because people are the weakest link in an entity’s security posture. Entities use technical hardware and software to implement security controls at several levels. However, all it takes is for 1 employee to plug in a virus-infected flash drive, click on a phishing email link, or hold the door open for an unauthorized individual to bypass technical controls in place.

Some entities (27%) had inadequate network, boundary, and data protection processes.

- A network firewall serves as a protective barrier between an entity’s network (and the computers on that network) and the Internet. Entities should use updated firewall hardware and software, with rules and exceptions to control who gets access to their network. Logging and reviewing abnormal network traffic are other important controls. Sensitive data should be encrypted at rest (e.g. within a computer or server) and in transit (e.g. when transferring the data to another location outside the network). Lastly, entities should have anti-malware mechanisms and ensure that media with sensitive information is sanitized and destroyed properly.

- Because a network firewall is often an entity’s first layer of defense, it is critical that its software is up to date with the latest security patches. Encryption and proper sanitation methods help ensure unauthorized individuals can’t assess or use sensitive data inappropriately. Lacking those types of preventative controls increases an entity’s security risk unnecessarily.

- Many entities had relatively strong controls in this area. However, some entities had major control issues:

- 1 entity didn’t have a firewall at all; instead, it relied on its intrusion prevention software.

- Another entity had numerous firewalls, most of which were using unsupported software or hardware at the time of the audit.

- 3 entities lacked sufficient encryption on laptops, either based on officials’ testimony or on our testing of a handful of judgmentally selected machines. A 4th entity’s staff had administrative rights, which allowed them to turn off encryption and other control settings.

- Most entities also didn’t have sufficient or any documents to show a recently decommissioned computer had been properly sanitized or destroyed.

- Implementing robust network, boundary, and data protection controls helps shield entities from cyberthreats as well as insider risks.

Some entities (27%) did not adequately protect their electronic backup data.

- Entities should maintain backup data with the same controls as their original data, including encryption at rest and in transit. Backup data should be “air-gapped”, meaning not connected to the network, in case entities’ systems get compromised and networked data becomes unavailable. Backup data should be located sufficiently distant from the main data. Lastly, entities should test backup data annually to ensure the data is not compromised and can be restored when needed.

- Without adequate encryption, entities risk their backup data being accessed and used by unauthorized individuals. When entities don’t have robust and comprehensive backup processes, they risk prolonged downtime that could include irrecoverable data loss if a significant security incident or weather-related catastrophe makes the primary data unusable.

- Most entities had isolated findings in this area, although many entities lacked an offline copy, and several kept their backup data in the same area or close to their main data. And 4 entities had major or significant control issues due to compounding problems, such as:

- lacking evidence that backup data was encrypted at rest or in transit. At 1 entity, we learned their backup data was kept in a locked data center, but the rack with the entity’s data was not locked and accessible to other data center tenants.

- lacking testing. None of the 4 entities formally tested their backup data.

- lacking copies of data. None of the 4 entities had air-gapped backup data.

- While these controls may not always be prioritized in daily operations, they represent the ultimate line of defense when a serious event compromises an entity’s main data.

3 of 12 entities had poor access or environmental controls for their data centers (25%).

- Entities typically use data centers to house their critical information systems. Data centers should have controls to limit who has unescorted access to them. They also should prevent or limit damage from environmental hazards, such as water, fire, temperature, and humidity.

- Poor data center access controls increase the risk that individuals could lose, damage, or steal assets or data. Entities that use data centers with poor environmental controls risk data loss from fire or water damage. These problems could severely disrupt the entity’s ability to provide services.

- 3 of the 15 entities we audited over the past 2 years did not rely on physical data centers. Instead, they used cloud services to store their information, which we did not assess. Of the remaining 12 entities with physical data centers or data closets, 3 had findings resulting in major or significant control issues. For example:

- 1 entity maintained a data closet within a ground floor office with an unalarmed window. That data closet also lacked water detection and humidity monitoring systems.

- A second entity’s data center had an unreasonably high number of employees with access. The access list included several former staff and the entity could not show access was properly revoked or that badges were recovered from 4 former staff. That data center also lacked water and humidity controls.

- A third entity did not maintain a list of authorized staff for its data center and didn’t track when data center keys were issued or returned. That data center also lacked a water detection system.

- Poor data center access controls increase the risk that individuals could lose, damage, or steal assets or data. Entities that use data centers with poor environmental controls risk data loss from fire or water damage. These problems could severely disrupt the entity’s ability to provide services.

A few entities (20%) had inadequate account security controls.

- Account security controls are designed both to limit and track who has access to an entity’s network and data. Basic controls for this area include rules on the length and complexity of account passwords, how frequently passwords should be changed, and how many times a password can be entered incorrectly before the account is locked. This control prevents hackers from trying numerous passwords until they find one that works (“brute force”). Other fundamental controls involve requiring system identifiers to be unique and for those identifiers not to include signs of the user’s privilege level (i.e. JSMITH_ADMIN). Additionally, accounts with elevated privileges should require Multi-Factor Authentication (MFA).

- Generic accounts make it difficult to identify who made changes. As a result, investigating security incidents may be more challenging. And account security processes integrate with other controls, such as security awareness training and network boundary controls.

- Another control requires user accounts to be disabled or deleted when staff leave employment. Of the 15 auditees, 3 entities had major control issues in this area. Other entities also failed individual account security control tests.

- Several entities did not meet basic password setting requirements. Problems ranged from limited failed settings to categoric failures. For example, some entities had no or weaker lockout requirements but complied with other requirements. One entity had weak lockout requirements and only required passwords to be 8 characters long but required complexity. Yet another entity’s password settings failed length, complexity, and lifespan requirements. This, combined with no lockout restrictions, increased the entity’s brute force attack risk considerably.

- Several entities did not disable accounts belonging to former employees in a timely manner or at all. For instance, 1 entity had 2 active accounts belonging to former employees at the time of our audit. Those employees had left the agency 2-3 months prior to our test. For at least 4 entities, we learned former staff accounts had been disabled, but documentation was unavailable to confirm this was done timely.

- Most entities failed various user identifier and MFA requirements. At two-thirds of the entities, we identified generic accounts ranging from 1 to over 100. We also found user account names indicating they had higher privileges at several entities. Lastly, more than half of the entities did not require MFA authentication for users with administrative privileges.

- When account security controls are weak, it is easier for unauthorized individuals to circumvent them and gain access to an entity’s network and data.

Review of Specific Information Technology Systems

8 of 12 entities had major or significant security issues with one of their IT systems we evaluated.

- In addition to the general areas discussed earlier, we also reviewed a smaller number of controls for a specific IT system that maintained or processed confidential or sensitive data for most of the auditees. This included systems for vendor management, licensing processes, investigation or complaint management, evidence collection, or training records.

- Specifically, we evaluated access controls such as proper system identifiers, password settings, least privilege principles for account users, system risk assessment, change control processes, and revocation of access for users who leave employment. Three entities either did not have a stand-alone IT system with sensitive data or were about to replace such a system with a modern platform. We determined a review would have limited value, so did not evaluate a system at these 3 entities.

- Two-thirds of the entities had major or significant security control weaknesses relating to their specific IT systems. Others had moderate issues. Below are more details of what we found:

- Systems had poor access controls: Many entities’ systems had between 1 and 25 active generic system user accounts. Many entities also had poor user password controls for the system we tested. This included weak or no lockout thresholds for failed login attempts and inadequate password length, complexity, or lifespan controls. For example, at 1 entity we noted length and complexity settings hadn’t been set up at all, while another entity allowed system users to use a single character password.

- Systems lacked adequate least privilege principles. Several entities couldn’t or didn’t periodically review when accounts had last logged into the system. For 1 system, we uncovered numerous test accounts with highest permissions to edit all system data. The entity was not aware that the developer had created those test accounts. At another entity, we found that over 20% of accounts appeared to be dormant—that is, they did not appear to have been logged in to for at least 90 days, while another auditee had a nearly 40% dormancy rate. 6 entities had active user accounts for staff who no longer worked at the entity.

- Systems lacked change control processes. Change control processes ensure that making significant system changes are deliberate and documented. They also ensure that entities have a backup plan to roll back any such changes, if they don’t work. Several entities lacked technical controls or documented change control policies to prevent or monitor such changes.

- Systems we reviewed lacked risk assessments. This was the case for nearly all entities for which we reviewed a specific IT system.

- Generic accounts create accountability issues because it is difficult to assign responsibility to those who made changes. Reviewing accounts that aren’t regularly used is useful to identify and deactivate unnecessary accounts that would otherwise present an entry point. Documented change management processes are critical to ensure system changes are made deliberately and are consistent with management decisions. Without that process, system changes may be unintentional, haphazard, or incomplete. Risk assessments are a strategic planning tool that helps entities evaluate and mitigate potential threats.

- The results in this section show security weaknesses exist not only on an entity-wide basis, but more importantly on systems that hold some of the most sensitive data these entities administer. Without proper account management, systematic change control and risk management processes, entities face increased risks of security incidents affecting those systems.

Conclusion

Our IT security audit work over the past 2 years revealed significant weaknesses in several security control areas across the 15 entities we audited. Auditees consistently struggled in 5 areas: vulnerability remediation (scanning and patching computers), continuity of operations & disaster recovery planning, incident response, management process and review, and specific IT system compliance. These themes are consistent with issues we identified in our prior IT summary reports that covered the last 10 years. Problems appear to be the result of 3 main factors: insufficient management oversight, lack of adequate IT resources, and poor contractor administration.

State and local entities could face significant consequences if hackers are able to access an entity’s network or confidential data because of poor security controls. A significant security breach could disrupt an entity’s mission-critical work, and its reputation would be damaged. A breach also could require costly customer credit report monitoring and could create legal liabilities or financial penalties.

The state has taken several steps to strengthen security by passing and revising the 2018 Cybersecurity Act, centralizing IT staffing and services through the Office of Information Technology Services (OITS), revising statewide technology policies, and providing increased funding to KISO. However, this and previous audits demonstrate that state agencies and local entities need to continue to work on improving their security. This is especially important as the shortage of IT security professionals appears to be worsening.

Recommendations

We did not make any recommendations for this summary audit. All entities we audited during the past 2 years received individual recommendations to fix the problems identified. Based on our follow up to the 2024 audits, entities generally had fixed or were in the process of remediating their findings. Follow-up work for entities audited in 2025 will take place in 2026.

Appendix A – List of Audited Entities 2024-2025 IT Security Audit Cycle

This appendix includes the list of 15 entities we audited between January 2024 and December 2025. The list includes each entity’s expenditures and Full Time Equivalent (FTE) positions.