Reviewing Counties’ Costs and Obligations to Meet State Requirements

Introduction

Representatives Shannon Francis and Adam Smith requested this audit, which was authorized by the Legislative Post Audit Committee at its April 10, 2025 meeting.

Objectives, Scope, & Methodology

Our audit objective was to answer the following question:

- How much did a selection of counties spend in 2024 to comply with state requirements for a selection of services, and how much of this spending was offset by state, federal, or user fee funding?

To answer this question, we talked to officials and reviewed fiscal year 2024 documentation and data from Gove, Johnson, and Labette counties. This included reviewing things like invoices and accounting records showing what the counties spent to provide a selection of 3 services required by state law. As part of this work, we also reviewed accounting records showing the revenues the counties collected while providing these services. Finally, we talked to county officials to gather their opinions on how the mandates we reviewed affected their counties and potential improvements the state could make.

More specific details about the scope of our work and the methods we used are included throughout the report as appropriate.

Important Disclosures

We conducted this performance audit in accordance with generally accepted government auditing standards. Those standards require that we plan and perform the audit to obtain sufficient, appropriate evidence to provide a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives. Overall, we believe the evidence obtained provides a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on those audit objectives.

Our audit reports and podcasts are available on our website www.kslpa.gov.

We estimate the 3 counties we reviewed spent $28.8 million providing a selection of 3 services in fiscal year 2024, which was partially offset by $9.7 million in state, federal, and user fee funding.

Background

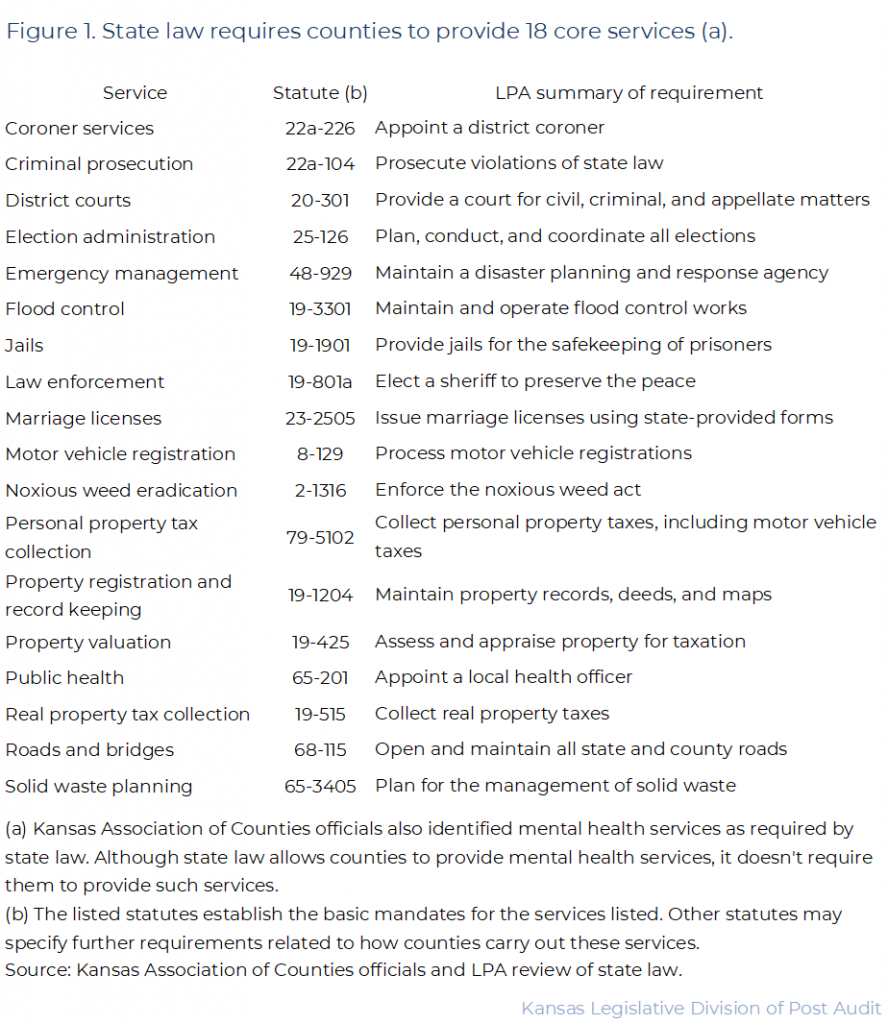

State law requires counties to provide a variety of core services, such as election administration, law enforcement, and motor vehicle registration.

- We reviewed state law and talked to officials from the Kansas Association of Counties to identify services counties must provide. We focused on core services that are more likely to be expensive or burdensome. State law also authorizes counties to provide minor services, such as removing vegetation that may obstruct drivers’ views at intersections (K.S.A. 19-2612). We excluded these minor services because they’re not likely to be expensive or burdensome.

- Figure 1 outlines the 18 core services we identified in state law. As the figure shows, state law requires counties to provide services like election administration, law enforcement, and several types of tax collection.

Counties are primarily funded by local tax revenue, and they generally use this revenue to cover the costs of providing the services state law requires.

- Counties’ revenues come primarily from local taxes, such as property and sales and use taxes. For example, in fiscal year 2024, 69% ($316.2 million) of Johnson County’s general fund revenues came from taxes. Similarly, 67% ($2.0 million) of Gove County’s fiscal year 2024 general fund revenues came from taxes.

- The remainder of counties’ general funds come from several smaller sources, which vary by county. They include things like user fees, investment earnings, and intergovernmental transfers, such as state or federal funds for things like public health. For instance, 13% ($58.9 million) of Johnson County’s fiscal year 2024 general fund revenues came from user fees, 9% ($42.1 million) came from intergovernmental transfers, and 7% ($32.0 million) came from investment earnings. Similarly, 19% ($578,000) of Gove County’s fiscal year 2024 general fund revenues came from user fees, 13% ($376,000) came from investment earnings, and 2% ($57,000) came from intergovernmental transfers.

- Although state law requires counties to provide the core services in Figure 1, it generally doesn’t provide funds specifically to support those services. Instead, counties use the revenues they collect from other sources to cover these costs. Kansas Association of Counties officials estimated that more than half of counties’ annual spending relates to providing services required by state law.

We selected 3 core services and 3 counties to review.

- Our audit objective was to determine how much a selection of services costs counties to provide. To do this, we selected 3 of the 18 core services listed in Figure 1 to review. These services were criminal prosecution, real property tax collection, and personal property tax collection, including motor vehicle taxation and registration. When tracking their finances, the counties we worked with combined real and personal property tax collection into ad valorem tax collection and separated out motor vehicle registration. As such, we group them this way for the rest of the report.

- To select these 3 core services to review, we focused on some of the services Kansas Association of Counties officials said were likely to be expensive or burdensome to provide. We also focused on services likely to be consistent across counties. For instance, state law (K.S.A. 19-801a) exempts counties with consolidated city and county law enforcement from the requirement to elect a sheriff. By contrast, all counties are required to collect ad valorem taxes.

- To select 3 counties to review, we focused on variables we thought might be relevant to the 3 services we’d selected. We selected Gove, Johnson, and Labette counties to review. We chose counties that varied in terms of their populations, geographic locations, and county spending per capita. We also chose counties that had varying crime rates and amounts of ad valorem tax revenues. Of the counties we selected, Johnson County is the largest in terms of population, total spending, and ad valorem tax revenues, whereas Gove County is the smallest. Because we didn’t choose these counties randomly, we can’t project our results to other counties.

We worked closely with county officials to determine how much the 3 counties spent to provide the 3 core services during fiscal year 2024.

- We worked with the clerks, treasurers, and county or district attorneys to identify their fiscal year 2024 costs for the 3 services we selected. This included things like reviewing accounting records to estimate staff salaries and benefits for the hours they spent working on these services. It also included reviewing invoices for service-related costs like printing, postage, newspaper notices, specialized software, and legal fees.

- To determine how the counties covered these costs, we reviewed accounting records to determine which funds they used. We also reviewed any revenues they collected while providing the services that might help offset their costs. These include things like user fees or fines the 3 counties collected. In these cases, the clerks, treasurers, and county or district attorneys didn’t keep the fee revenue. Instead, they deposited the revenue in their counties’ general funds, helping offset the cost of providing these services. Johnson County also received a small amount of state and federal grant funding to cover the costs for specific services provided by the district attorney.

- We couldn’t verify some of the costs and resource requirements counties reported to us, but we think they’re reasonable estimates. Johnson County’s recordkeeping was the most sophisticated overall. But the 3 counties didn’t always precisely track how many hours staff spent on each service. For instance, treasurer staff spend time on ad valorem tax collection, motor vehicle registration, and other functions. The counties also didn’t comprehensively track how much of shared office costs like printing or postage went to each service. We asked county officials to estimate the staff time and shared office resources used for the 3 services we reviewed. We think their estimates are reasonably accurate because the 3 counties’ estimates largely aligned with each other, and officials could explain any meaningful differences. The counties’ estimates also generally aligned with what we expected based on our prior conversations with the county officials’ statewide associations.

Selected Service Costs

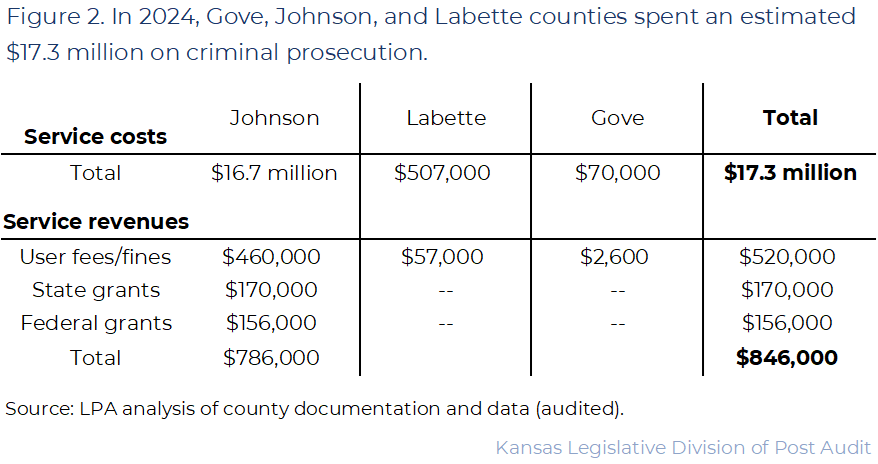

In total, we estimate the 3 counties we reviewed spent $17.3 million on criminal prosecution in fiscal year 2024, which was slightly offset with $846,000 in grants and user fees.

- State law (K.S.A. 19-702, 22a-104) requires county and district attorneys to prosecute violations of state law on the state’s behalf. Of Kansas’s 105 counties:

- 99 counties elect a county attorney. Beyond criminal prosecution, county attorneys may do things like advise the board of county commissioners or draft county contracts. This may be a part-time position in rural areas, and 1 attorney may serve as the elected county attorney for several counties at once. Other county attorneys may have staff attorneys and other support staff to help carry out their duties.

- 6 counties elect a district attorney per state law (K.S.A. 22a-101, 22a-108, 22a-109). These 6 counties are Douglas, Johnson, Sedgwick, Shawnee, Reno, and Wyandotte. District attorneys exclusively handle criminal prosecution for the single county that elected them. They have staff attorneys and other support staff to help carry this out.

- The top portion of Figure 2 shows how much the 3 counties we reviewed spent on criminal prosecution in 2024. As the figure shows, we estimate these counties spent $17.3 million in total. The 3 counties’ 2024 spending ranged from just $70,000 for Gove County to $16.7 million for Johnson County. For all 3 counties, these costs were primarily for staff salaries and benefits, with much smaller amounts for things like office equipment, attorney training, and witness fees.

- The bottom portion of Figure 2 also shows how much these counties collected in revenues directly related to this service. This primarily reflects fees collected as part of diversion agreements. State law (K.S.A. 22-2907) gives county and district attorneys discretion to offer diversion agreements to people charged with crimes. These agreements allow people to avoid criminal convictions if they meet certain requirements. In return, they pay fees set by the county or district attorney.

- As the bottom portion of the figure shows, the 3 counties collected $520,000 in fees, helping offset a small amount of county costs. As the figure also shows, Johnson County collected $170,000 in state grant funds and $156,000 in federal grant funds. Johnson County was the only of the 3 counties to receive these types of grants. For instance, the county received a grant from the federal Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms, and Explosives and a grant from the Kansas Department of Corrections for the county’s juvenile diversion program. Johnson County officials said they applied for these grants and that other counties could, too.

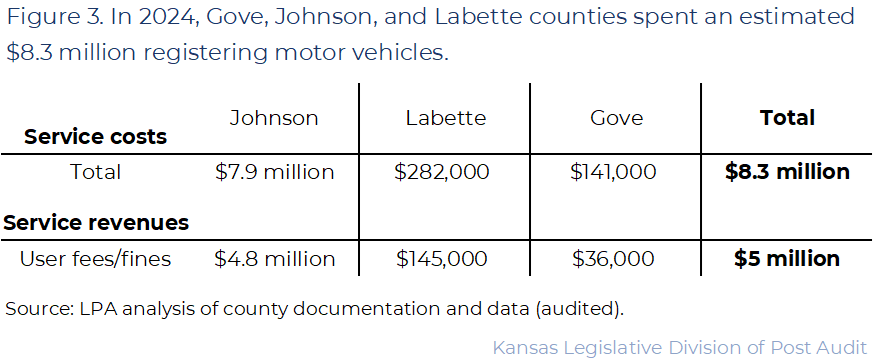

In total, we estimate the 3 counties we reviewed spent $8.3 million providing motor vehicle registration services in 2024, which was partially offset by $5.0 million in user fees.

- State law (K.S.A. 8-129) requires treasurers to process motor vehicle registrations on the state’s behalf. Doing so requires things like processing registration applications, checking for proof of insurance, and collecting and distributing taxes and fees. Carrying out these duties would also require maintaining at least 1 walk-in office location where they could take place.

- The top portion of Figure 3 shows how much the 3 counties we reviewed spent on motor vehicle registration services in fiscal year 2024. As the figure shows, we estimate these counties spent $8.3 million in total. This ranged from $141,000 in Gove County to $7.9 million in Johnson County. These costs were primarily for staff salaries and benefits, with much smaller amounts for things like walk-in offices, printing, postage, and office equipment.

- State law (K.S.A. 8-145, 8-145d) allows counties to retain certain user fees they collect during vehicle registration. The rest of the fees they collect are remitted to the state. For example, counties retain $2 of each title application fee they collect. They also collect service fees such as a $5 county service fee and up to a $5 facility fee.

- The bottom portion of Figure 3 shows the amounts of fees counties retained in fiscal year 2024 related to this service. In fiscal year 2024, the 3 counties collected a total of $34 million in motor vehicle registration fees. As the figure shows, the counties retained $5.0 million of those fees. This helped offset about 60% of the $8.3 million in total spending for the 3 counties.

- None of the 3 counties received any state or federal funding to support motor vehicle registration.

In total, we estimate the 3 counties spent $3.2 million collecting ad valorem taxes in fiscal year 2024, which was fully offset by $3.9 million in user fees and fines.

- State law (K.S.A. 19-515, 79-1801) requires treasurers to collect ad valorem taxes for all the taxing entities in their counties. Based on how the 3 counties we reviewed track their finances, ad valorem taxes include real and personal property taxes, excluding those related to motor vehicle registration. The taxing entities include the county itself, as well as the state, cities, townships, school districts, and others.

- To facilitate this, state law (K.S.A. 79-1803) requires county clerks to calculate the ad valorem tax rate that should be levied on each piece of real and personal property in the county. The clerk bases these rates on each taxing entity’s budget. They use these budgets to determine how much ad valorem tax revenue each taxing entity needs to cover its costs.

- The clerk provides the taxing entities’ tax amounts to the treasurer, who collects the taxes from the property owners. Property owners pay all the taxing entities’ rates at once, as shown on their annual tax statements. The treasurers’ tax collection process includes things like printing and mailing these statements to property owners and taking steps to pursue delinquent taxes. Finally, treasurers distribute the tax revenues they collect on behalf of other taxing entities back to those entities.

- The top portion of Figure 4 shows how much the 3 counties we reviewed spent on ad valorem tax collection in fiscal year 2024. As the figure shows, we estimate these counties spent $3.2 million in total. This ranged from $157,000 in Labette County to $2.8 million in Johnson County. Gove County’s costs for this service were larger than Labette County’s costs despite having a smaller population. Gove County officials said their higher costs were because of the large number of mineral rights in their county. Officials explained collecting mineral rights taxes can be labor intensive and therefore costly. That’s because mineral rights are often separated from other real property and can be divided between multiple owners. As with the other 2 services we reviewed, the counties’ costs were primarily for staff salaries and benefits. The 3 counties also spent much smaller amounts on things like printing, postage, and specialized software.

- The bottom portion of Figure 4 shows how much these counties collected in revenues directly related to this service. In this case, user fines primarily reflect interest charged on delinquent ad valorem taxes. State law (K.S.A. 79-2004, 79-2004a) requires counties to charge interest until delinquent taxes are eventually paid. User fees may also include small amounts from other fees allowed by statute.

- As the figure shows, the 3 counties collected $3.9 million in fees and fines related to ad valorem tax collection. This ranged from $45,000 in Gove County to $3.6 million in Johnson County. Johnson and Labette counties collected more than enough to cover their total ad valorem tax collection costs. But this isn’t a reliable funding source. That’s because whether and how much counties collect in fees and fines depends on the number of property owners repaying delinquent taxes, which is likely to differ each year.

- None of the 3 counties received any state or federal funding to support ad valorem tax collection.

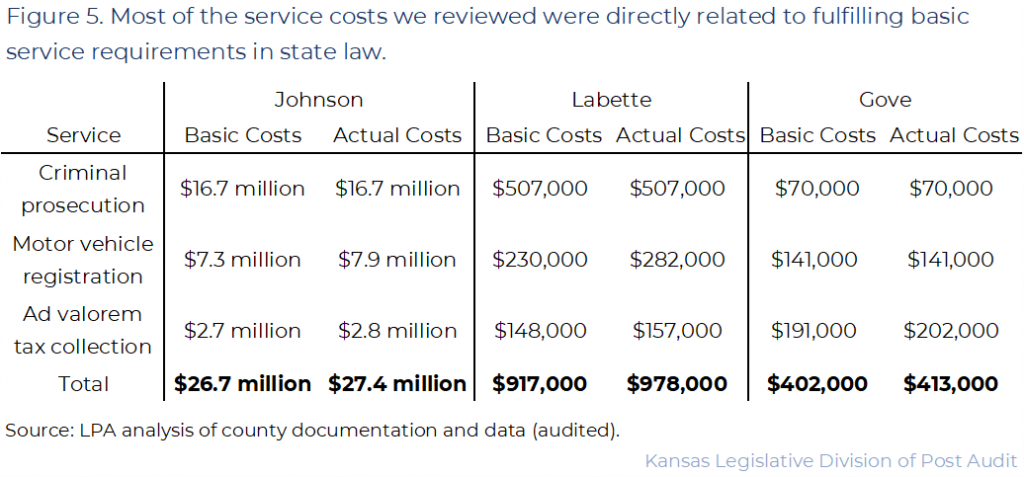

The 3 counties’ costs for the 3 services we reviewed were generally related to meeting requirements in state law.

- We also reviewed whether counties might be spending more than they’re required to under state law. For example, every county needs at least 1 walk-in motor vehicle office to provide a physical location where the required services can take place. In some cases, this could simply be space in a county treasurer’s office. But some counties may choose to have additional offices or provide extra services such as an online payment option. These things would be beyond the minimum state law requires. We reviewed state law to determine the basic level of service counties must provide under state law. Then, we compared the estimated costs to provide those basic services to what counties spent, including any enhanced services. We didn’t evaluate the appropriateness or efficiency of every expense, such as whether the county had the right number of staff or was wasteful with its printing or postage.

- Figure 5 compares what the 3 counties spent on the services we reviewed with the costs to provide the basic level of service required by state law. As the figure shows, the 3 counties’ spending was largely related to providing the basic level of services. We assumed all criminal prosecution costs were necessary to provide the basic level of services because county and district attorneys have significant discretion over how they perform this service.

- In this report, we focus on the counties’ actual spending (not only their spending on the basic level of service) because county officials said their extra costs were needed to provide effective services. For example, Figure 5 shows Johnson County spent an estimated $600,000 on its motor vehicle registration service beyond the minimum required by statute. This included things like $225,000 to lease a second walk-in motor vehicle office and $57,000 for an electronic payment service. Treasurer officials said these things reduced wait times and helped the county provide adequate service to its residents. Even with these enhanced services, Johnson County’s average wait time is 3 hours. This suggests these costs may be necessary for motor vehicle registration to function as state law intended in a county as populous as Johnson County.

We estimate it would cost the state $19.1 million to cover the 3 counties’ fiscal year 2024 costs for the services we reviewed, but this likely isn’t consistent each year.

- As part of our audit objective, legislators asked us to estimate how much funding the state would need to contribute to cover counties’ total costs for the 3 services we reviewed. Overall, we estimate the state would need to contribute $19.1 million to cover the 3 counties’ fiscal year 2024 costs for those 3 services. This includes all county costs, including the enhanced services county officials said are needed to provide effective services. This funding would be on top of the service-related revenues the 3 counties received in fiscal year 2024. These revenues are outlined in Figures 2-4.

- However, covering counties’ costs may require more or less than $19.1 million in other years. That’s because the costs of providing the 3 services and the revenues counties collect while providing them may not always be predictable or regular. For instance, Johnson County officials said labor market changes might affect staff salaries, which make up the largest costs associated with these services. Alternatively, a recession could affect a county’s crime or ad valorem tax delinquency rates.

Other Findings

Officials from the 3 counties we reviewed told us state process improvements would be more helpful than additional state funding.

- We talked to officials from the 3 counties to gather their opinions on how the costs to provide the 3 services affect their counties. Many officials said it would be helpful to receive more state funding in the sense that having more money typically makes it easier to address county priorities, like lowering taxes. Some said they wouldn’t want more funding from the state because they were concerned it could lead to the state trying to exercise more influence over the counties.

- Instead, the officials we talked to said it would be more helpful for the state to improve some of its processes than to provide more funding, especially for motor vehicle registration. For instance, Johnson County officials said the state’s requirement that motor vehicle titling be done in person is burdensome. They suggested replacing this with electronic titling, as some other states have done. Johnson County officials estimated motor vehicle titling requires more staff time each year than any other single process. They didn’t estimate how much time electronic titling would save.

- County officials also said they were frustrated with the software the state requires them to use.

- Officials from all 3 counties said they dislike the MOVRS motor vehicle registration system. They said this system is slow and unreliable and makes their jobs more difficult. This is particularly true at the end of each month, when the volume of activity spikes and the system is prone to crashes. County officials didn’t estimate how much staff time such crashes cost.

- Officials from Johnson County also pointed to issues with the Odyssey court filing system. They said this system is less efficient than the proprietary system they used before. For instance, it requires manual data entry, which their old system didn’t. They also said it created new security risks, as shown in Odyssey’s 2023 breach. This breach exposed about 150,000 people’s sensitive personal data from appellate court and judicial administration files. Officials from the other 2 counties said the system was fine for their purposes but recognized this was probably due to their much smaller case volumes. Gove County officials said they had been using paper files before, so they saw Odyssey as an upgrade.

- Despite these challenges, county officials said they should continue providing the 3 services, rather than the state providing them instead. They said their counties’ residents would receive worse customer service from state-administered services. They said this would likely include longer wait times, less convenient walk-in office locations, less proactive assistance, and more mistakes. Officials also told us each county has its own priorities for criminal prosecution, which county-level services allow them to pursue.

Other estimates for counties’ motor vehicle registration service costs used reasonable methods but differed from ours because we had more detailed and updated data.

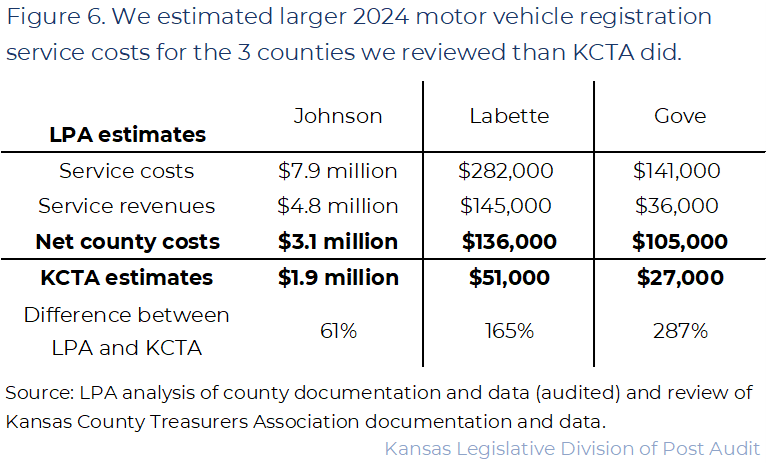

- In March 2025, the Kansas County Treasurers Association (KCTA) provided the House Transportation Committee with estimates of all 105 Kansas counties’ 2024 motor vehicle registration costs. We talked to KCTA and reviewed documentation and data to understand KCTA’s methodology for creating their estimates. We compared this methodology to ours to determine why our estimates might differ from theirs.

- Figure 6 compares KCTA’s estimated net county costs for motor vehicle registration to our estimated net county costs for the 3 counties we reviewed. As the figure shows, the net costs we estimated were between 61% (Johnson County) and 287% (Gove County) higher than KCTA’s estimates.

- We couldn’t evaluate how KCTA’s estimates might compare to ours for all 105 counties, so we can’t say whether KCTA’s estimates for other counties might also be underestimated. Although KCTA used reasonable methods to create their estimates for the 3 counties we reviewed, there are a few reasons why KCTA’s net cost estimates were lower than ours.

- First, KCTA based their estimates only on self-reported data that may have contained errors. For example, officials from 1 county we reviewed told us they made mistakes in the data they gave KCTA. This included things like leaving out staff benefit costs and incorrectly categorizing certain revenues. We requested things like accounting records and invoices, allowing us to verify counties’ costs and revenues rather than rely on self-reported data.

- In addition, KCTA’s cost data wasn’t as detailed as the documentation and data we used. For instance, KCTA simply requested bottom-line wage totals from the counties. By contrast, we asked county officials to provide complete salary and benefit information for each staff member and to estimate the number of hours each spent on each service.

- Finally, KCTA used 2023 data and applied 3% inflation to estimate 2024 costs and revenues. This rate reasonably reflects the Consumer Price Index inflation rate over this period. But it doesn’t accurately reflect things like staffing changes made between 2023 and 2024. For instance, we included 6 Treasurer staff for Labette County in our estimates, whereas KCTA only included 5 staff.

Conclusion

State law requires counties to provide a variety of services on the state’s behalf. We reviewed how much it cost Gove, Johnson, and Labette counties to provide services related to criminal prosecution, motor vehicle registration, and ad valorem tax collection. Overall, the counties used a combination of their own tax revenues and user fees and fines to cover most of the costs of providing these services. The counties we reviewed received little to no state or federal funding to help cover these costs. We estimate that the state would need to contribute about $19.1 million to fully offset these 3 counties’ costs of providing the selected services we reviewed for fiscal year 2024. However, whether to provide additional funding and to what extent is a policy decision for the Legislature.

Recommendations

We did not make any recommendations for this audit.

Agency Response

On October 15, 2025 we provided the draft audit report to the clerks, treasurers, and county or district attorneys from Gove, Johnson, and Labette counties. Since we didn’t have recommendations for them, their responses were optional. Only the Gove County Attorney and Johnson County Treasurer provided responses, which are below. They generally agreed with our findings and conclusions.

Gove County Attorney Response

Legislative Division of Post Audit

800 Southwest Jackson Street

Suite 1200

Topeka, KS 66612

Dear Persons:

Thank you for the opportunity to review the “Reviewing Counties’ Costs and Obligations to Meet State Requirements” performance audit. I have been County Attorney in Gove County for about 9 months, but I have been County Attorney in Decatur County for nearly 37 years and serve as the County Attorney in Sheridan County – this is my second term. Michael Abbott, my Assistant County Attorney, also serves as County Attorney in Graham County. Gove County is unique among our counties in that there are 30 miles of Interstate 70 traversing through it. The result, from the perspective of the prosecutor, is that instead of 250 traffic cases in the other three counties, Gove County handles 1400 traffic cases. This puts a huge burden on us as prosecutors, and upon the courts. If the County were able to charge a surcharge on the tickets it would help underwrite the costs. I would also add that very few of those 1400 traffic tickets are written to people that live in the county. I don’t think that is because law enforcement is not writing tickets to them because of their residential address, but just simply because the volume of traffic is overwhelming. I acknowledge that Interstate 70 provides some economic opportunities, including sales tax collection, for Gove County that other counties that are not on the interstate highway system do not have, however a small surcharge on the traffic tickets for small counties with a large segment of interstate would go a long way to helping us underwrite the costs of the burden that interstate does put on us from a prosecution standpoint.

Sincerely Yours,

Seven W. Hirsch

County Attorney

Johnson County Treasurer Response

To: Andy Brienzo, Principal Auditor

Kansas Legislative Division of Post Audit

From: Thomas Franzen, Johnson County Treasurer

Re: Response to Legislative Post Audit report – Reviewing Counties’ Costs and Obligations to Meet State Requirements

I’d like to thank the Legislative Post Audit team for their work on this audit. My comments are specifically addressing the motor vehicle title and registration services mandated by the state of Kansas to provide these services as an agent of the Kansas Department of Revenue.

Regarding the motor vehicle component of the report, the audit points out differences between the counties providing motor vehicle services, both in cost and level of services provided.

As the audit points out, cost structures are different across the state. Specifically, labor is the largest cost component to providing the services, and labor markets are different across the state. These differences lead to significantly different cost structures across 105 counties providing these services. Correspondingly, standardized fee structures to fund these services don’t make sense in today’s world. A standardized fee structure approach may have made sense when KDOR was performing a significant portion of the work, but that changed in 2012 with the implementation of the MOVRS system, where significant work was transferred to county treasurers.

A fee structure that allows local governments to charge fees necessary to provide the desired level of customer service is what is needed now. The County Service fee is the primary fee funding the operation and should be the fee that is allowed to be set at levels determined locally. Accountability for the County Service fee charged could be established with the County Treasurer or the Board of County Commission. These are the officials that receive the majority of feedback from constituents and should be given the ability to address that feedback through service level provision. Currently, local officials are at a disadvantage given the current practice of having a standardized County Service fee. Allowing that fee to be set at the local level makes more sense, since that is where the service is actually being provided.

Again, I would like to thank the Legislative Post Audit team for their work on this audit, and I look forward to working with the Legislature to craft sound, customer-focused legislation that allows local governments to charge appropriate fees to provide this critical state-mandated service.